Original Article, Preprints.org, Version 1, November 2024.

Abstract

The measurement problem in physics remains an unresolved challenge characterized by significant conceptual complexity. Paradoxically, mainstream scientific discourse has often sidestepped this issue by invoking processes such as the ‘collapse of the wavefunction’—a mechanism that, to this day, lacks a rigorous definition. This framework has primarily served as a pragmatic way to bypass the problem, allowing the inherent subjectivity introduced by the observer to be overlooked.

In this article, I aim to provide a detailed exposition of the measurement problem and trace its underlying causes. A case will be made for integrating perspectives from the Philosophy of Science to address this issue systematically. Furthermore, I will explore the critical necessity of developing a robust theory of consciousness, which may provide deeper insights into the measurement problem. By investigating the foundational principles of such a theory, this work seeks to illuminate the intricate relationship between Quantum Theory and Consciousness, potentially offering a more unified understanding of these fundamental phenomena.

Introduction

Since its inception, quantum theory has faced persistent criticism due to its fundamentally revolutionary concepts, such as wave-particle duality, indeterminism, and non-locality. These principles directly challenge traditional notions of how physical systems are expected to behave, often conflicting with the deterministic and localized frameworks of classical physics.

Quantum physics began as a groundbreaking paradigm with Max Planck’s revolutionary proposition in 1900, which introduced the frequency dependence of energy, marking the birth of quantum mechanics. However, this can be considered a culmination of several ideas before Planck, especially the works of Boltzmann involving Blackbody radiation.

In 1905, when Einstein explained Hertz’s 1887 discovery of electromagnetic waves using his theory of the photoelectric effect, the quantum idea gained further validity because it could be easily verified through an experiment. However, it was only when the theory was more structured and organized as a semi-classical description of the physical system that it started receiving more attention. Bohr’s model of the atom was an important consideration in this regard.

The idea that a true world exists out there and that a scientist’s work is only to create models of the true world based on her observations is not new. Plato pioneered this idea by distinguishing between the Ideal and the Real world.

He held the Ideal (world of Forms) to be superior—something that can only be apprehended through reason and intellect—while the Real world of sensory experience was merely a reflection of human limitations.

Almost two thousand years later, Galileo’s work on the Scientific Method provided a framework for how science should be done. The process was to examine the phenomenon as fully as possible and to quantify the sensed data into mathematics. To evaluate how successful this process of quantification was, one could devise an experiment aimed at testing the predictions of the model.

The scientific method also incorporates Descartes’ dualistic distinction between mind and body.

For a scientific model to approximate objective truth, it has to be unbiased and free of measurement errors. And this is only possible when a physical description can be made without any reference to the mind. Occam’s razor plays an essential role within the scientific method—minimizing variables of observation improves the model’s accuracy. However, minimization should not be done at the cost of losing representation of the actual phenomenon.

Before the quantum theory of the form we know today, Maxwell’s Electrodynamics and Newton’s and Galileo’s Classical Mechanics, including Einstein’s SR and GR, were the most dominant physical theories of the world, and all of these were deterministic. So, even for empirical experimentation, one could easily apply the equation of motion, make predictions, testify, and verify the model.

The question:

“Does the world exist when nobody is observing it?”

was not even considered valid within these frameworks. The objective existence of the physical world was not merely assumed but viewed as an essential presupposition for deterministic theories to operate. Thus, the answer to such a question was both implicit and necessary:

➡️ “Yes, it ought to be.”

The Role of Philosophy in Science

The philosophy of science plays a crucial role in shaping scientific progress, serving as a guiding framework for scientists grappling with foundational questions.

Einstein’s Special theory of Relativity

A notable example of this can be observed in the development of Einstein’s Special Relativity.

The search for a hypothetical medium called ‘aether’ played a crucial role in guiding the foundations of Special Relativity.

- If not for the null result of the Michelson–Morley experiment, Einstein might never have felt the need to unify Maxwell’s Electrodynamics with the Lorentz transformation equations.

- Consequently, the first postulate of Special Relativity—the constancy of the speed of light—may not have emerged as a cornerstone of the theory, and the physical theories we know today could have been different.

Paradigm of Dark Energy

Another example is of “dark energy.”

Despite the absence of direct empirical evidence, dark energy is a central element of the standard model of cosmology, widely accepted and actively utilized in scientific discourse.

This highlights the enduring impact of philosophical considerations in shaping scientific paradigms.

It illustrates how philosophical frameworks can bridge gaps in empirical understanding, driving the evolution of scientific theories.

Different Ancient Philosophies

Ancient Greek philosophers are revered for their original ideas that continue to influence modern science.

Among their many contributions is the concept of composite structures in the universe.

Many of these philosophers posited that the cosmos is comprised of fundamental elements like air, water, and fire. Remarkably, our contemporary understanding of the universe parallels this notion, as our physical theories are built upon the idea of a composite structure involving elementary particles such as quarks, leptons, and bosons.

Similarly, the Greek philosophers’ exploration of perfect geometrical structures laid the groundwork for the concept of ‘self-evident’ or ‘axiomatic’ truths’.

- These truths were considered so intuitively obvious that formal proofs seemed unnecessary.

- Alternatively, their avoidance of proofs may have stemmed from the inherent complexity of demonstrating formal proofs within their logical systems.

🔹 This could hint towards modern mathematical theories, including Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem.

Furthermore, Zeno’s paradoxes, which highlight the challenge of distinguishing between motion and rest states (at consecutive times) of a moving arrow,

offer groundwork for the analysis of rest and motion in Einstein’s Special Relativity.

In light of these discussions, the philosophy of science emerges as a guiding force in our scientific endeavors,

showing pathways for exploration and discovery.

The purpose of any ultimate science extends beyond merely explaining how things work.

When probability measures are considered, there is mounting evidence that a universe like ours is highly unlikely.

Thus, an ultimate science must also explain this anomaly.

The anthropocentric perspective falls short in providing satisfactory answers.

- It limits our understanding by placing humans at the center of the universe,

- Potentially obscuring broader truths and possibilities.

To address such profound questions, we must:

- Expand the scope of scientific inquiry to include broader philosophical considerations,

- Actively integrate insights from the philosophy of science.

In either case, the philosophy of science remains crucial in guiding scientific endeavors.

Regrettably, some prominent physicists, such as Hawking and Weinberg, have expressed skepticism regarding the relevance of philosophy to scientific progress, potentially underestimating its role in guiding foundational inquiries.

The Measurement Problem

The inherent indeterminism of quantum physics marked a significant departure from classical notions, leading many physicists, including Einstein, to challenge its validity.

In quantum mechanics, observation fundamentally alters a system’s outcome.

“We can’t observe quantum systems without disturbing them.”

Bohr, adopting a positivist stance, asserted that:

“Reality doesn’t exist independent of observation.”

This viewpoint directly challenged the concept of objective reality as traditionally conceived in the scientific method.

Kant’s Influence on Quantum Reality

By the 1920s, the notion of objective reality had been heavily influenced by Kant’s Transcendentalism \cite{Kant_1998}.

🔹 Kant posited that while the true nature of things as they exist independently of perception (the noumenon) remains unknowable,

🔹 We can nonetheless acquire objective knowledge of phenomena as they appear through our cognitive framework.

Bohr seems to have been influenced by this idea of Transcendentalism, as noted by Honner \cite{Honner1982-HONTTP-2} and Faye \cite{Faye1993-FAYNBA-2}. However, at times, Bohr has contradicted himself with his Positivist arguments.

While Bohr’s ideas on Correspondence and Complementarity evolved over time,

there was never truly a debate about the nature of reality, but rather about:

➡️ How the subjectivity of the measurement process should be reconciled within the quantum framework.

Bohr’s Complementarity and the Observer’s Role

By the 1930s, Bohr was firmly convinced that:

- The observer could never influence the outcome of an experiment.

- He extended the concept of Complementarity to incorporate the experimental setup as an integral part of the system.

Despite this, critics have accused Bohr of:

- Clinging too rigidly to the realism of classical physics.

- Dismissing quantum realism as merely a logical construct.

This deep conviction in the supremacy of Correspondence Principle may explain why:

- The role of observation in quantum physics was never taken too seriously.

- Even in the face of new spin statistics (which is strictly based on quantum mechanics),

Bohr still clung to the classical realism framework.

🔹 Nevertheless, the Correspondence Principle undeniably played a crucial role

in guiding the early development of quantum theory.

This inability to reconcile the role of observation in experiments

with the quantum mechanical framework led to the emergence of what is now known as:

➡️ “The Measurement Problem.”

If we look at the modern understanding of science*, an electron is not a point-like particle in the way Bohr imagined. The best representation of an electron is in terms of probability waves. The electron’s manifestation as a particle or a wave depends on the specific experimental context.

This view aligns more closely with the philosophy of conscious realism than with Bohr’s entity realism.

- The act of measurement, as defined by the experimental setup (as proposed by Bohr and colleagues),

seems to determine whether an electron appears as a particle or a wave. - This suggests a deeper link between observation and the nature of reality.

Conscious Realism and the Future of Physics

This understanding, coupled with several other ideas in physics, hints towards a deeper, generalized understanding of the physical world based on conscious realism, where:

🔹 Observation itself is deeply intertwined with the very fabric of reality.

Perhaps this could go beyond the conventional spacetime fabric, as neuroscientists like Hoffman \cite{article} suggest.

This approach could, in principle:

- Solve the measurement problem

- Provide a new paradigm shift in how we perceive the universe

➡️ More on this in the next chapter.

Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

In 1925, Werner Heisenberg formulated his matrix mechanics and, two years later, introduced the concept of quantum indeterminism through his uncertainty principle, which sharply contrasted the assumptions of classical physics.

Bohr, however, viewed this relationship through the lens of his Complementarity, as noted by Faye \cite{copenhagen}.

🔹 Bohr even interpreted wave-particle duality as another manifestation of this Complementarity.

Born’s Probability Interpretation

In 1926, Max Born’s probability interpretation of the square of the wavefunction provided a solid theoretical foundation for quantum theory.

This interpretation allowed the wavefunction to be understood as contributing to representing probabilities.

The EPR Paradox

The challenges posed by the EPR paradox -presented by Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky in 1935 -prompted Bohr to restrict the scope of Complementarity to the system’s kinematical and dynamical properties. Faced with these challenges and the inability to define the role of quantum indeterminism in experimental outcomes led to a pressing need for an interpretation of the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics.

The Emergence of the Copenhagen Interpretation

Between 1925 and 1950, various views emerged describing the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics.

However, it was only in 1955 that Heisenberg used the term:

➡️ “Copenhagen Interpretation (CI).”

According to Heisenberg’s CI:

- The act of measurement affects the observation.

- To perform a measurement, a measuring apparatus is needed.

However, the details of the measuring apparatus are unspecified, meaning that even a physical system could act as one. It also means that the measurement process has nothing to do with the individuality of the observer, as asserted by Pauli \cite{pauli1994writings}.

This aligns with Bohr’s idea of “The Individuality” or “The Unified Whole” of the atomic process, where the measuring system is viewed as part of the system being observed by the means of entanglement.

Wavefunction Collapse and Reduction of State

With this interpretation, the Copenhagen Interpretation (CI) attained a means to get away with the wavefunction through a mysterious collapse associated with observation.

🔹 Nevertheless, Heisenberg never used the word “collapse.”

Instead, he viewed it as:

“Reduction of state” of the wavefunction that occurs once a system is observed by the apparatus.

By redefining the process in this way, the subjectivity associated with observation could also be eliminated.

According to CI, Heisenberg’s uncertainty relation was not a limitation of knowledge in the classical sense, but rather a feature of the new ontology of Quantum Mechanics.

Bohr’s Indefinability Thesis and the Limits of Formal Systems

The idea that the kinematic/dynamical properties of atomic systems cannot be described without reference to the experimental apparatus is also known as:

➡️ Bohr’s Indefinability Thesis.

This thesis has a stark resemblance to the Incompleteness Theorem.

One could argue that within the formal system of quantum mechanics, hints emergence of a higher theory—one that encapsulates the observer’s subjectivity as an integral aspect of the reality being observed.

Such a theory might involve:

- An axiomatic reconstruction of quantum mechanics, refining:

- The Copenhagen Interpretation’s “collapse of the wavefunction.”

- Heisenberg’s “reduction of state.”

- Alternatively, it could reflect a fundamental limitation in the logical structure of quantum physics.

All these assumptions seem more plausible than the “absurdity of Schrödinger’s cat.”

These realizations point towards a theory of consciousness, one that:

✅ Incorporates the subtlety of the observation process.

✅ Reconciles existing theories into a coherent framework governed by the scientific method.

The Need for a Higher Theory of Consciousness

The idea of generalization and simplification isn’t merely a tool for physicists; it extends to all natural processes, which appear to be governed by fundamental laws.

Physicists often discuss the concepts of beauty and symmetry in physical laws, believing that there must exist a higher theory that unifies all fundamental forces.

This pursuit of unification can also be seen as an extrapolation of present ideas in modern physics concerning the four fundamental forces.

When it comes to the study of consciousness, it is essential to define it within the framework of these forces that we understand so well.

The Challenge of Unifying Physical Theories

Many physicists have noted that successful scientific theories like Quantum Theory and General Relativity are fundamentally incompatible.

Among the four fundamental forces, we have achieved a good understanding of how to unify three of them—

but gravity remains an outlier.

One approach to unifying these forces is to address their incompatibility within the frameworks of Quantum Physics and General Relativity.

This would require revising one or both theories at a fundamental level.

Such revisions would pave the way for:

- A unified theory that provides the right tools for the theory of consciousness.

- A deeper understanding of the physics behind the collapse of the wavefunction.

Many of the important scientific theories of the past century were developed in an attempt to resolve paradoxes within existing frameworks. In fact, such paradigm shifts define scientific progress, as Kuhn \cite{Kuhn1962-KUHTSO-3} rightly notes in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

A New Paradigm Shift in Physics

Another possibility for the unification scheme of forces could lie in:

➡️ A new paradigm shift that goes beyond merely resolving incompatibility. but transcending it.

Given that both Quantum Mechanics and General Relativity have been:

✅ Verified by numerous experiments

✅ Confirmed with remarkable accuracy

A necessary revision will not just resolve their incompatibility or the existing paradoxes within them but generalize and transcend them or: ➡️ Extend beyond the framework of these theories.

This would make our current successful theories special cases of a more fundamental framework.

This is an exciting time in the history of physics.

I would argue that the paradigm shift of this magnitude in our understanding of the cosmos has been due for almost a century.

Two Approaches to the Theory of Consciousness

Similar to the unification of fundamental forces, there are two general approaches to a theory of consciousness:

1️⃣ Consciousness as an Emergent Property

One approach is to contemplate a theory of the physics of consciousness.

🔹 Seminal works by:

- Penrose and Hameroff (Orchestrated Objective Reduction)

- Integrated Information Theory (IIT)

- Global Workspace Theory (GWT)

- And a few others

➡️ All suggesting the physics behind the emergence of consciousness from physical processes.

These theories share a common goal:

✅ Exploring the underlying mechanisms by which consciousness arises from neural and physical activity.

However, they all face challenges, particularly due to:

- The difficulty in reconciling quantum mechanics’ probabilistic nature

- The deterministic nature of classical physics, especially in the context of measurement and observation

2️⃣ Consciousness as a Fundamental Entity

On the other hand, we could consider consciousness not as an emergent property but as a fundamental entity,

as suggested by the works of Hoffman \cite{article}.

By embracing this perspective, we enter a new paradigm of physical theories:

➡️ Grounded in the dynamics of consciousness.

🔹 All theories that suggest consciousness as an emergent property are plagued by:

The Hard Problem of Consciousness.

However, when conscioussness is viewed as a fundamental entity, we get away with the Hard Problem, because physical processes emerge from consciousness and not the other way around.

Thus, the direction of causality is reversed, leading to a fundamentally different perspective on reality.

Framework of Theories of Consciousness

A significant portion of the forthcoming discussion operates at the conceptual level.

While some assertions may initially appear speculative, they are grounded in scientific consensus.

Indeed, contemporary science often traces its origins to the realm of ideas and conjectures.

In this section, I have discussed some of the postulates of the new theory of consciousness.

Postulate 1:

Subjective experience of consciousness is unique and, therefore, can’t be mimicked by any physical processes.

The big question regarding this thesis is whether we can address the Hard Problem of Consciousness, which involves resolving the anomaly of how the subjectivity of conscious experience emerges from a system of logic and physical processes.

This subjective experience is also termed qualia, and by definition, it seems that no matter how sophisticated a system of proofs is, a super-scientist Mary will never feel the experience of seeing the color red solely with objective descriptions like wavelengths and color.

Thus, it does not make sense to seek a theory of consciousness unless we:

- Have a mechanism to resolve this limitation of the Hard Problem, OR

- Accept it as a consequence of the new theory of consciousness.

➡️ I presume that the Hard Problem is not a problem at all but a standout feature of any theory of consciousness.

The Distinctive Nature of Consciousness:

The irreducibility of consciousness makes it fundamentally unique—

It cannot be mimicked or reproduced by any physical system or logical framework.

Consciousness is inherently special because it:

✅ Operates as the governing force behind this proposed new physics.

✅ Transcends the boundaries of purely physical or computational models.

If the Hard Problem were to be “solved” in a way that reduces consciousness to physical processes, then the uniqueness of conscious experience would be lost.

The only conceivable way to replicate the subjective experience of consciousness is to create another system that itself possesses consciousness.

➡️ This insight highlights the fundamental distinctiveness of consciousness as not merely an emergent property, but as a unique and irreducible phenomenon within the framework of reality.

Postulate 2:

The laws of physics governing consciousness are Quantum Mechanical and beyond.

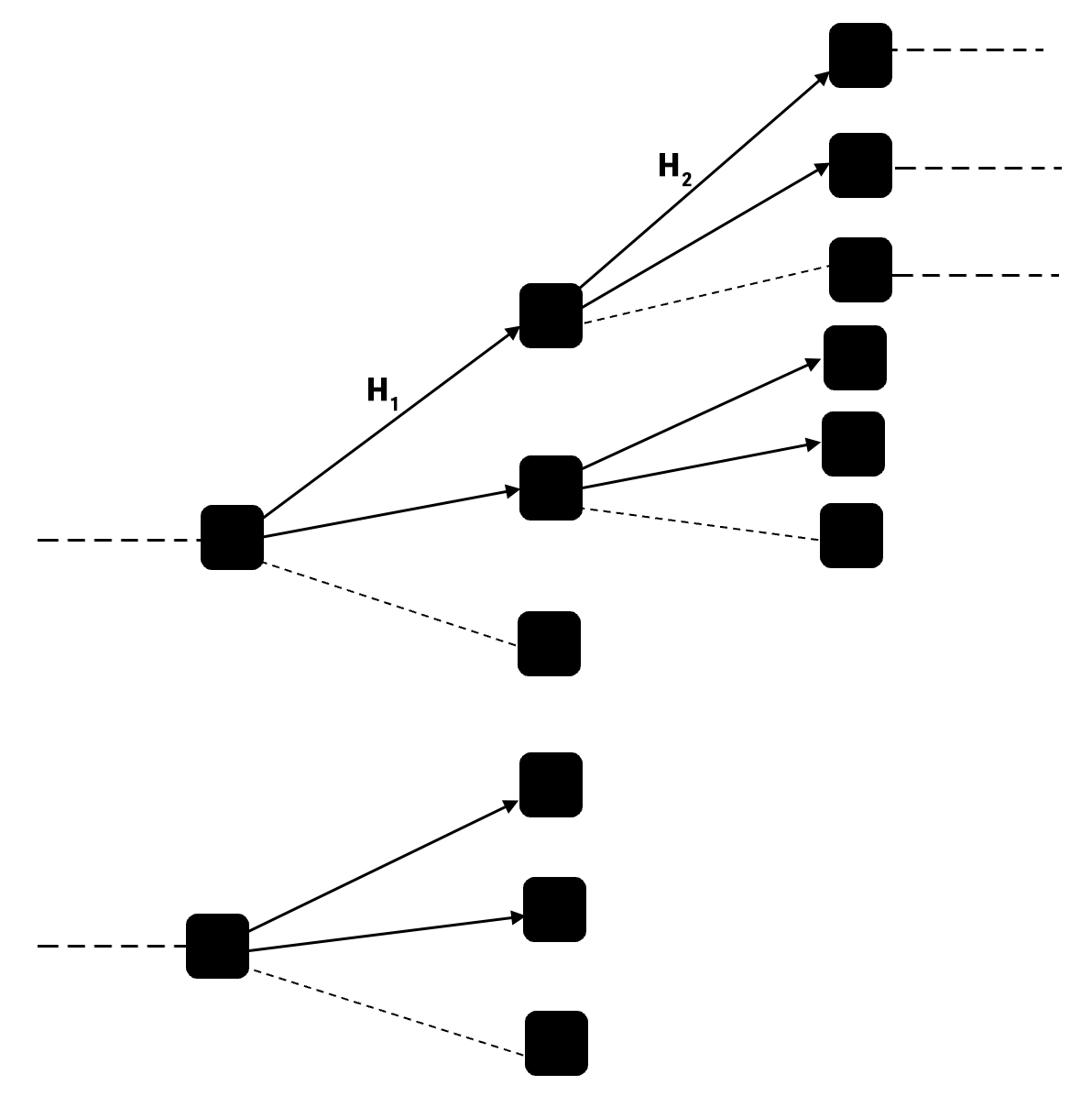

Figure 1: Probability Space of Consciousness

The quantum theory is considered to describe the underlying system at the most basic level.

Therefore, any theory of consciousness must also be consistent with the quantum mechanical description.

🔹 As a result, non-locality, indeterminism, and duality are fundamental properties of the theory of consciousness.

Several Quantum Mechanical formulations of consciousness propose that consciousness:

✅ Arises due to complex interactions and dynamics of quantum fields within the brain.

One notable work is discussed by Ricciardi \cite{Ricciardi1967}.

However, rather than viewing consciousness as an exclusive process occurring in the brain,

we should see the human brain as merely an image of a larger order of universal fundamental consciousness.

Mathematical Framework for Consciousness:

A conscious initial state transitions to a conscious final state under a Hamiltonian governed by the dynamics of conscious experience.

Since Quantum Field Theory is valid, a simple transition amplitude equation given by the Fermi-Golden Rule can also be applied here:

$$ \Gamma_{i\rightarrow f} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar}|\braket{f|H_n|i}{}| \rho(E_f) $$

As shown in Figure 1, the probability space of conscious experience is inspired by:

- Hoffman’s network of conscious agents.

- The combined ideas of Hoffman et al. \cite{article} and Ricciardi & Umezawa \cite{Ricciardi1967}.

A transition occurs due to a perturbing Hamiltonian under conscious experience.

➡️ Depending on the strength of the perturbation, the system either:

✅ Makes finer energy corrections in the same initial state, OR

✅ Evolves into a new final state, as dictated by quantum mechanics.

Any physical experience that amplifies or inhibits this transition does so by altering the Hamiltonian.

According to the uncertainty relation, time dictates whether there is coherence or decoherence in conscious experience.

Between these initial and final states (represented by nodes), lies the subjective conscious experience.

Postulate 3:

Intelligence guides the time evolution of a conscious system. The equilibrium of a conscious system doesn’t have any physical significance unless there is intelligence.

In the physical universe, equilibrium is a fundamental state achieved through:

- The minimization of energy.

- The pursuit of stability.

This principle often governs the time evolution of physical systems.

However, in the context of a conscious system,

➡️ Intelligence introduces a purposeful dynamic that transcends the purely physical imperative for equilibrium.

The Role of Intelligence in Consciousness:

Driven by intent and will, intelligence can enable a conscious system to:

✅ Act contrary to the equilibrium state in pursuit of higher-order objectives.

The influence of intelligence is inherently:

- Domain-specific

- Contextual

Possible Objectives of Intelligent Consciousness:

The motivations of an intelligent conscious system may include:

🔹 Survival and reproduction

🔹 Understanding and awareness

🔹 Value and meaning

➡️ The possibilities are endless.

Conclusion and Future Scope

A pivotal result in quantum mechanics, Bell’s theorem, addresses the fundamental incompatibility between the predictions of quantum mechanics and the assumptions of locality and realism that underpin classical physics.

Developed by John Bell in 1964, the theorem demonstrates that:

➡️ Hidden variable theories cannot replicate the statistical predictions of quantum mechanics without violating the principle of locality.

Since the theory of consciousness, as outlined in Postulate 2, aligns with quantum mechanics, it inherently incorporates non-locality.

🔹 This alignment enables the theory of consciousness to provide:

✅ Statistical predictions consistent with quantum mechanics

✅ Coherence with Bell’s inequalities

The Role of Conscious Experience in Quantum Mechanics

The key to this reconciliation lies in the introduction of a novel variable:

Conscious experience.

This variable represents a:

✅ Non-physical, non-local element

✅ Interacts with the quantum system during observation or measurement

Unlike classical hidden variables, which are deterministic and local, the conscious variable operates in a non-local framework, allowing it to:

➡️ Mediate quantum correlations

➡️ Without violating Bell’s theorem

In this sense, the conscious variable is neither a direct replacement for hidden variables nor a purely physical construct but an extension that complements the probabilistic and non-local nature of quantum mechanics.

Redefining the Role of Observation

This perspective does not merely assert the importance of non-locality but instead reframes the role of observation in quantum mechanics.

The conscious variable introduces a layer of interaction that:

✅ Governs the reduction of quantum states

✅ Addresses the subjectivity of measurement

Thus, this theory does not contradict Bell’s inequalities. Rather, it operates within a paradigm where:

➡️ Non-locality and consciousness are integral to the structure of quantum mechanics.

Final Thoughts and Future Research

In conclusion, this paper has explored:

- The intricate relationship between quantum mechanics, consciousness, and the philosophy of science.

- A framework where consciousness is treated as a fundamental variable.

- How this framework bridges the deterministic tendencies of hidden variable theories and the probabilistic, non-local nature of quantum mechanics.

By:

✅ Addressing the measurement problem, and

✅ Resolving the apparent incompatibilities between quantum mechanics and classical physics,

➡️ This theory extends the principles of quantum mechanics to include the observer’s subjective experience as an integral aspect of reality.

To establish this theory as a viable model, future research must focus on:

- Formalizing the mathematical structure of the proposed framework.

- Identifying empirical methods to validate its predictions.

If successful, this synthesis could transform our understanding of reality

and offer profound insights into the fundamental nature of existence.

References

- I. Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, in Critique of Pure Reason, P. Guyer and A.W. Wood (Eds.), The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant, Cambridge University Press, pp. 81–84.

- J. Honner, The Transcendental Philosophy of Niels Bohr, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A, Vol. 13, 1982, pp. 1–29.

- J. Faye and H.J. Folse (Eds.), Niels Bohr and Contemporary Philosophy, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993.

- D. Hoffman, Conscious Realism and the Mind-Body Problem, Mind and Matter, Vol. 6, 2008.

- J. Faye, Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

E.N. Zalta (Ed.), Winter 2019 Edition, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2019. - W. Pauli, C. Enz, K. Meyenn, and R. Schlapp, Writings on Physics and Philosophy, Springer, 1994.

Available at: Google Books. - T. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- L.M. Ricciardi and H. Umezawa, Brain and Physics of Many-Body Problems, Kybernetik, Vol. 4, 1967, pp. 44–48. Available at: DOI Link.