Understanding Infinity

Can a part be bigger than the whole?

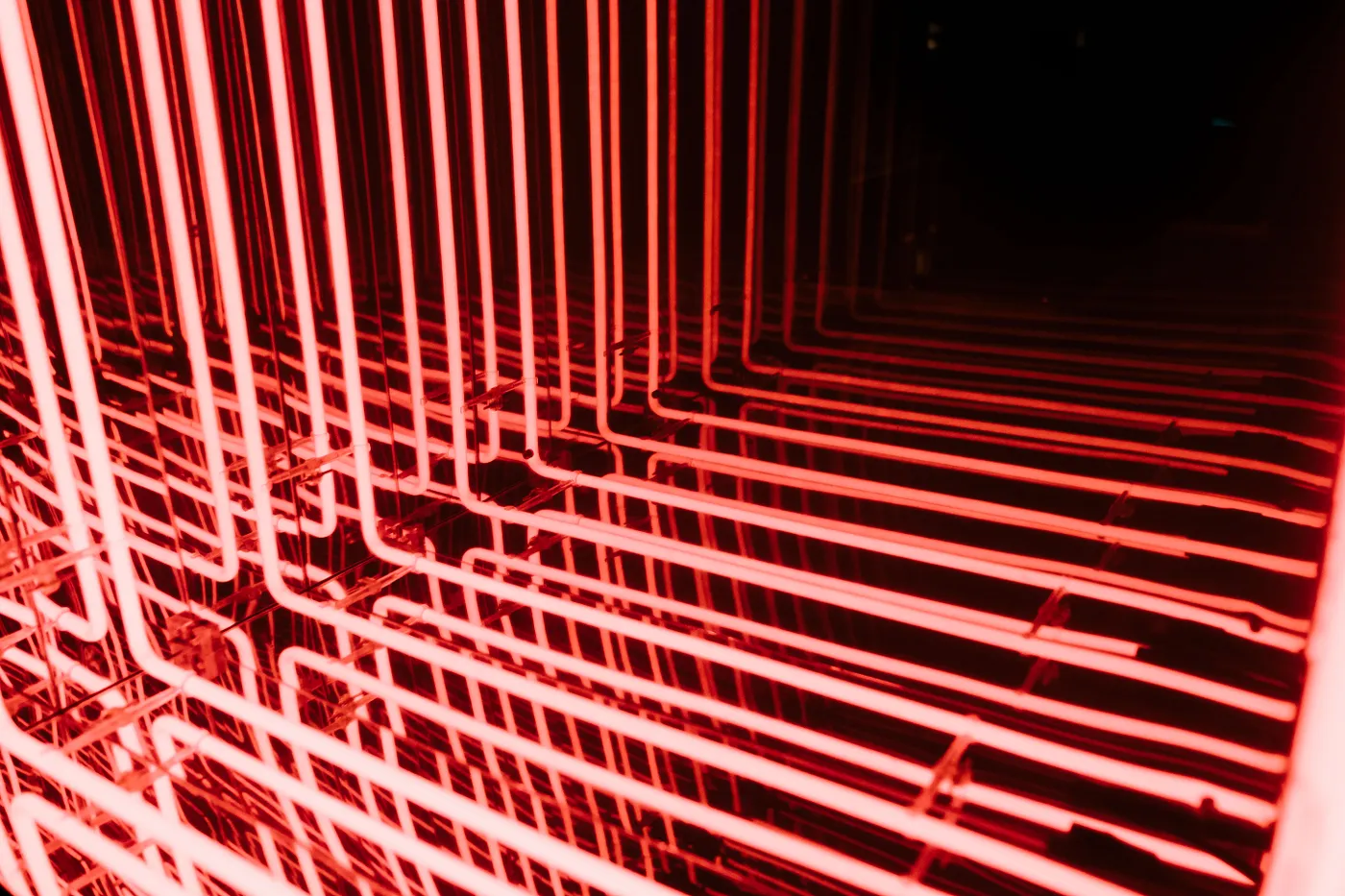

Photo by Danny Howe on Unsplash

Photo by Danny Howe on Unsplash

An Infinity in mathematics signifies an unimaginably large number, so vast that it can’t be expressed numerically. The work around this is to just represent it symbolically. Writing it down numerically would be a virtually impossible feat if an accurate representation of the number is desired without any approximations. Approximation can definitely ease it in a certain way. But if one can imagine an absurdly large number, one can also imagine a number larger than this one. For eg: If the first absurdly large number is represented by ’n’ (using approximations) instead of ‘infinity’, one can easily get to the next larger number ‘n+1’. And then repeat the process all over again to finally get a number that is absurdly bigger than the original bigger number we started from. Thus, making the use of ‘infinity’ as a symbol inevitable.

A Thought Experiment with Pizza

To better understand what an infinity is, consider this example. Imagine there is a big Pizza to be divided among 10 people equally. Each person would receive one-tenth of the pizza. Now, if the same pizza is to be divided among only 5 people, each will receive a larger portion of the pizza than before. If it is divided among only two people, each person will receive half of the pizza. As the number of people to whom the pizza is divided decreases, the size of the portion each person receives increases. If the pizza is divided among only one person, that person would receive the entire pizza. From this inductive reasoning, a law can be formulated: ‘As the number of parts into which a certain thing is to be divided equally. gets smaller, each part will keep getting bigger.’ Taking this law to its limit, if a certain thing is to be divided into zero parts, the size of each part is such that it gets infinitely bigger. This paradox of ‘can a part be greater than the whole?’ has two answers. First, it is impossible to consider ‘zero’ as a valid number of parts of something. Second, this is the domain of singularity, so naturally our general understanding and laws used to formulate those understandings would fail.

The Power and Pitfalls of Zero

The lesson we can learn from this is that zero is a powerful number, but it must be used carefully. It can have consequences, and in some cases, those consequences can be infinite. Mathematicians and physicists try to avoid this by framing their equations so that zero is not involved as to give infinities. However, there are times when an infinite result is unavoidable, such as an infinite time series. Talking about infinities, one immediate question is ‘are all infinities equal?’ It is not possible to answer this without knowing how big an infinity actually is, so in the following paragrapphs, let’s try that.

Counting Infinity: One-One Correspondence

We do not need to know explicitly how big something is to know if it is infinite or not. All we do is pair up these quantities with the sequence of natural numbers. This in the language of mathematics is called, One-One-Correspondence. If you can map, each of these quantities with some number sequentially (basically what I am doing here is. explaining how to do counting), the quantity definitely is infinite because eventually, that quantity is gonna pair up with the infinity of natural numbers. Thus, they have the same size.Well! Then lets come specifically to the topic, how can some infinities be bigger than the other infinities? How many numbers are there between any two natural numbers? To make things simple, how many numbers are there between 1 and 2? Well! There are 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, ……..1.8, 1.9. But there are also 1.11, 1.12,……1.31, 1.32, ……1.91, 1.92,…… But not just these, there are also 1.000000000000001, 1.0000000000000000012,………….1.999999999999998, 1.99999999999999999 and infinitely many other numbers too like 1.1745638464783963084628. It turns out that, there are infinite number of numbers between 1 and 2.

Are Some Infinities Bigger Than Others?

The question is… Is this infinity any bigger/smaller/equal to the infinite set of natural numbers? When we try to put each of these numbers between 1 and 2, into a one-one-correspondence with the set of natural numbers starting from 1, we can inductively see that not all real numbers are paired up with the sequence of natural numbers. The formal proof of this was carried out by Cantor in his Diagonal Argument. This is the case of being uncountably infinite. We say that the set of real numbers are uncountably infinite. There simply are too many of real numbers to pair up with natural numbers. This is how some infinities (infinities of real numbers) are bigger than other infinities (infinities of natural numbers).